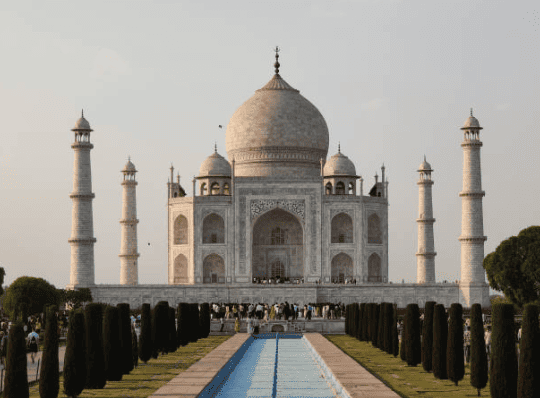

You might have often heard stories, both wonderful and less pleasant, about traveling in India. Tales of the majestic beauty of the Taj Mahal, the snowy mountains of Kashmir, or Mumbai, famously known as Bollywood for its film industry. All of these are located in central and northern India, regions that are already popular among Indonesians and frequently visited by them.

However, I chose to explore southern India, specifically the state of Tamil Nadu. My journey took me to its major city, Chennai, and the mountainous area of Kodaikanal in Dindigul. On the map, Tamil Nadu stretches across the southern tip of the subcontinent, bordering Kerala and close to Sri Lanka.

To reach Tamil Nadu, one must pass through Chennai, its capital, which offers a strikingly contradictory landscape. This metropolitan city presents two contrasting faces. On one hand, modernity is evident everywhere. On the other, a shabby, chaotic, and overcrowded environment still dominates.

Once known as Madras, Chennai is now the largest cultural, economic, and educational hub in southern India. It is the fourth-largest metropolitan city in the country, with a population of over eight million. The Chennai Metropolitan Area ranks as the 36th most populous urban area in the world. So, it’s no surprise that every corner of this 1,189-square-kilometer metro is always bustling with activity.

Starting at its gateway, Chennai International Airport, you’ll find crowds of people at the exit—waiting for relatives, friends, or guests. Taxi drivers eagerly offer their services, much like in Indonesia. The sheer number of people can feel overwhelming as you step out.

A similar scene unfolds on the train from the airport to the city center. People cram into the train, standing shoulder-to-shoulder. Those who can’t find a seat stand in the aisles or spill into the doorways. Don’t expect these trains to resemble the sleek ones in Japan or Singapore. If you’ve seen the movie Slumdog Millionaire, that’s a closer depiction of Chennai’s trains.

The same goes for city buses, especially during peak hours like morning commutes or evening rush hours. Buses are the most widely used mode of transportation, often filled to capacity. Those who can’t fit inside hang onto the doors.

During my first day in Chennai this past January, I discovered that government-run bus drivers were on strike. A local police officer and a resident confirmed this, explaining why few buses were running. Every bus that did pass by was packed with passengers. As a result, many of us had to wait hours for a ride or switch to the train. I opted for the train to reach the city center.

Despite being a metropolitan city, Chennai retains the charm of an old town. Many of its buildings display a worn, classic aesthetic—a mix of Mughal and British architectural styles known as Indo-Saracenic. This metro area has grown with a blend of Hindu, Islamic, and Gothic architecture. Even the earliest institutional buildings predominantly reflect the colonial era.

The colonial architectural style is evident in several iconic structures in Chennai. These include Fort Saint George, built in 1640, the Madras High Court, established in 1892, the Southern Railway Headquarters, Ripon Building; and the Government Museum. Other notable buildings include the Senate House of the University of Madras, Amir Mahal, Bharat Insurance Building, Victoria Public Hall, and the College of Engineering. These structures are typically painted either white or deep red, though many have peeling or faded paint.

In addition to the Indo-Saracenic style, there are also many Gothic-style buildings. Examples include the Chennai Central and Chennai Egmore railway stations. Chennai Central serves as a hub for all modes of transportation, encompassing train stations, bus stations, and soon, a metro station. Its architecture, marked by deep red paint, stands out prominently.

These buildings date back to as early as the 17th century, with some of the oldest still-standing structures built in the 7th and 8th centuries. Exploring the city evokes a sense of stepping back in time.

It’s reminiscent of Jakarta in the 1980s. This nostalgic feeling is heightened when observing city buses that cater to millions of residents. If you’ve seen the old Dono, Kasino, Indro movies from the 80s, you might imagine the buses in Chennai: faded, with peeling paint, plenty of windows but missing glass panes, allowing the wind to blow freely inside.

Amid the metropolitan setting, there are numerous slum areas, particularly along railway tracks. Shanties, often serving as permanent homes, line the streets. These tiny shelters usually consist of a single room without a bathroom. Residents often sit on the ground outside their homes, conversing. Daily life in Chennai is conducted in Tamil, a language distinct from Hindi, India’s national language. As a result, people from northern India often communicate with Tamils in English.

Homeless people sleep everywhere, often shocking visitors. They rest on sidewalks under the scorching sun or during rain, covering themselves with just a sarong. Even more surprising is the widespread habit of urinating in public—on the sides of roads, building walls, or next to vehicles. Sometimes, people line up to relieve themselves while standing.

This habit isn’t confined to adult men, children are also encouraged by their elders to urinate wherever they please. Even adult women sometimes follow this practice. On one occasion, I witnessed an elderly woman urinating near a trash bin while standing. It’s common to encounter the smell of urine while walking around the city.

Adding to this is the smell of garbage. Littering is widespread, leading to piles of trash in various places, including major roadsides. These piles often go uncollected for extended periods, emitting a foul odor. Stray cows rummage through the trash in search of food, scattering it further.

Similar scenes can be found in tourist areas, such as the beach. Chennai is home to Marina Beach, the second-longest urban beach in the world, stretching 13 kilometers along the Bay of Bengal. While the beach is popular, it is poorly maintained, with trash scattered across its sandy expanse. Comparatively, beaches like Trikora in Bintan or Mirota in Galang Island are far cleaner and better managed.

Despite Chennai’s grimy exterior and the habits of its residents, the city has achieved significant progress. Chennai International Airport, the main gateway to southern India, is the fourth busiest airport in the country. Acknowledging the influx of tourists, the Indian government has developed a relatively grand airport here, reminiscent of Sultan Hasanuddin Airport in Makassar or Kualanamu Airport in Medan.

Access to the city center is easy, with various modes of transportation available. Elevated roads and urban tollways crisscross the city. The airport has been connected to intercity trains and the metro since as early as 1939, predating Jakarta’s airport train, which only started operating recently.

The Chennai Metro Rail (MRT) also serves the airport, albeit only partially, covering a few kilometers and not yet reaching the city center. Since 2016, stations and routes to the airport have been operational, and construction to expand the metro continues.

Other transportation options include taxis, including ride-hailing services like Uber and Ola. While debates over ride-hailing services were ongoing in Indonesia, Chennai had already embraced them. At Chennai International Airport, designated pickup zones for these services make it convenient for passengers arriving late at night.

Despite its challenges, Chennai attracts tourists with its rich cultural heritage. In 2015, the travel guide publisher Lonely Planet listed Chennai among the top ten cities to visit globally. That same year, the BBC named Chennai the “hottest city” for its blend of modernity and deeply rooted cultural values. Lonely Planet also ranked Chennai as the ninth-best cosmopolitan city in the world.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.